Propaganda then and now

Notes of a lecture by Nicky Hager at Auckland Museum on Wednesday, 2 May 2007.

Nazi poster 1

I will be talking tonight about the history and characteristics of propaganda, starting with the WWII versions as seen in the “Towards the Precipice” poster exhibition here at the museum and moving on to contemporary examples that together help us to understand the world we live in.

It would be easy to imagine that propaganda started somewhere like the German Nazi regime. Actually, text books on the subject explain that it was earlier in the 20th century: the US advertising industry. The last 100 years have seen growing sophistication of techniques spreading from selling products into other areas of human activity incuding religion, war and politics.

Nazi poster 2

In the early 1930s, Hitler and Goebbels leapt at the power of propaganda to build poltiical support and marginalise their opponents. They established the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda – thereby giving the word Propaganda the connotations it has had since. I don’t need to recount the history. As Berthold Brecht wrote, “where one burns books, one eventually burns people”.

Definition of Propaganda – originally it was a neutral description of political messages. Some countries still use the term in this sense, eg Spain and Portugal. It comes literally from the Latin, meaning roughly “things that must be disseminated”.

In popular discussion, it is often used to mean little more than “the slogans/words of my opponents with which I do not agree”, as in….. “that’s just a load of propaganda”’

But the word has an important and informative meaning.

The key is to understand the diffrence between propaganda and persuasion. Persuasion is the use of words, arguments, pictures etc to persuade or reinforce and point of view and to change behaviour. It can be an honest, informative, democratic activity.

Propaganda is persuasion, but involving deception and falsehoods. The purpose is manipulation, not information. Or sometimes confusion as a tactic. There are many documented types, such as negative stereotyping of groups of people and scapegoating; and techniques of tapping into fears, envy and insecurities to manipulate people’s beliefs and actions. These characterise some or the Nazi propaganda but – unfortunately – just as much some of the modern-day examples I’ll discuss.

Not surprisingly, we recognise the Nazi posters as propaganda more than the Allies ones,

All races together poster 3

but ones like this British poster fit the definition of Propaganda too. This was a time that the British actions in colonial India and elsewhere were far from being equals working together, but this wartime propaganda was designed for the purpose of drawing other nations into the British war effort.

Also not all the Bill Sutch posters in this exhibition fit the usual defn on propaganda – eg

Keep it under your hat poster 4

is a legitimate communication for public information.

The key to the Nazi posters was simplicity and repetition.

Blossoms poster 5

The thinking behind this is seen in the writing of Joseph Goebbels 50 years earlier. He said that ‘the rank and file are usually much more primitive than we imagine’ and political messages ‘must therefore always be essentially simple and repetitious’. In the long run, he argued, someone can only achieve results in influencing public opinion if they ‘reduce problems to the simplest terms’ and have ‘the courage to keep repeating them in this simplified form despite the objections of intellectuals’.

Compare this to the words of one of the National party strategy advisers quoted in my recent book The Hollow Men about that party.

He wrote (quoting US Republican strategist David Horowitz): ‘Politics is a War of Emotions. For the great mass of the public, casting a vote is not an intellectual choice, but a gut decision, based on impressions that may be superficial and premises that could be misguided. Political war is about evoking emotions that favour one’s goals. It is the ability to manipulate the public’s feelings in support of your agenda, while mobilising passions of fear and resentment against your opponent.’ In this war, he argued, ‘the most potent weapons’ were anger, fear and resentment. ‘Remember that swing voters are not partisans, do not relate to politics as a political war and can barely tell the difference between the parties.’

He really wrote that – and acted it out in the advice he gave and speeches he wrote. This was a man named Peter Keenan who almost never appeared in the news media but who, over a three year period, had more influence over that party than most of its MPs. The National Party strategy advisers (and no doubt Labour Party ones too) returned repeatedly to the importance of repetition of simple slogans to get through to groups of voters they described as “the punters out in punter land”.

It is illuminating to look at some of the theory of propaganda. As I wrote about in the book, researchers have concluded that repetition works, and endlessly repeating simple slogans works , precisely because they do not strongly engage our brains, meaning that we do not apply our experience and intellect to consider whether they are true.

It works this way, according to an American textbook on propaganda, because ‘we see and hear many, many persuasive messages each day, and we see and hear them over and over again. It is difficult to think deeply about each and every one of these communications’ and ‘repetition is thus left to create its own truths’.24 Complex messages and reasoned two-sided debate have a completely different effect on our brains. They stimulate thought and help us to reach our own judgement. That is the basis of genuinely democratic politics but it is not the aim of propaganda.

The 1940s posters employed simplicity and repetition, but propagandists have found that the perfect medium for propaganda is film with music. The first famous example of this was the Nazi propaganda film called “triumph of Will” by the young German film producer Leni Riefenstahl. She made films of heroic, strong and beautiful Germans, including soldiers marching in the shape of a swastika.

As you all know, fast moving TV and film images, accompanied by music, are a favourite medium of modern-day advertisers too.

Books on propaganda explain why moving images accompanied by music are so effective. As explained in The Hollow Men, advertising and propagandists want to find methods to get around our natural scepticism about sales talk and our tendency to think of counter-arguments when someone is trying to persuade us. The simplest solution found for this is mild distraction. Research has found that when simple, repeated messages are accompanied by ‘distractions’ such as music, humour, striking images or fast-moving film, it blocks or reduces our natural tendency to construct counter-arguments and so makes the message more persuasive. Big distractions do not work, because they get in the way of our even noticing the message; and even mild distractions do not work with complex messages. The ideal messages to bypass our intellects and get inside our heads are the simple repetitive ones where our attention is caught (distracted) by the music, moving pictures, surprising images and humour.

In the growing Cold War of the late 1940s, the use of propaganda if anything intensified. George Orwell’s writing from that era remains some of the most insightful analysis of propaganda – especially his books Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty Four. They tell us a lot about the world we live in today.

Nineteen Eight-Four slide

Think about the plot of 1984. The book desribed Oceania (part of which is Britain, that is known as Airstrip One) which is engaged in an enternal war with Eastasia. There is constant news of victories, while the war drags on, and any news stories from the past that contradict the current propaganda are systematically destroyed. Reality is managed by the Ministry of Truth, Ministry of Plenty, Ministry of Love and Ministry of Peace. As journalist Robert Fisk has written, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are reminiscent Oceania’s war with Eurasia, bolstered by lies and propaganda.

In contrast to the Vietnam War, which was described as the most televised war, the Afghanistan and Iraq wars have been the most media managed. The US has literally thousands of military people employed as press staff to stop journalists reporting freely and to try to ensure that the news is favorable to the US government and its allies.

Chomsky/Manufacturing Consent slide

But the most insidious propaganda is naturally tha propaganda that we are unaware of. Noam Chomsky argued in the 1988 book Manufacturing Consent that western societies are shaped by systematic propaganda. He wrote that “the 20th century has been characterised by three developments of great political importance: the growth of democracy, the growth of corporate power and the growth of corporate propaganda as a means of protecting corporate power against democracy.”

I would argue that this is the main political issue of our times. Chomsky describes private news media as primarily businesses selling a product (readers and audiences – meaning market shares — rather than news ) to other businesses (ie advertisers).

The growth of this new private form of propaganda is seen in the colossal growth of PR companies. A not very visible but profound change has been occurring…. More and more political issues, party politics and even Government business is being determined by PR advisers. A New Zealand example is the Government’s CARBON TAX proposal. After months when nearly allt he news coverage was negative about the tax, the Government backed down. Guess who behind it? A university researcher found that most of the opposition, and news stories, came from a well organised and funded campaign by a coal industry lobbyist.

This happens on issue after issue.

Secrets and Lies slide

Researching this book made me aware of these issues of public relations influence. I was leaked in effect the file room of a United States PR company that was working for the state-owned logging company Timberlands West Coast (TWC). In public TWC said it needed a PR firm to just have its say in public, but I found: a fake ‘community’ front group set up by the PR company (arguing that logging was good for the forests), buying of scientists with lucrative grants, and far from just having their own say, huge effort to silence critics (legal threats, trying to stop environmentalists’ funding, causing trouble for outspoken scientists and ecologists and so on.

This is the main and hugely pervasive form of modern propanganda. In WWII, it was only governments. Now it is any interest that can afford to pay for the PR companies, lobby firms, government relations legal firms etc. We probably all know people doing PR jobs – they are usually quite defensive about what people think of their profession. I talk each year on ethics to PR students and reassure them that PR can by ethical, socially useful work – clear good communications – or it can be part of undermining democracy as paid voices crowd out all others, and propagandist techniques and messages become normalised.

George Orwell slide

Propaganda can be blatant (like media campaigns claiming the enemy is developing weapons of mass destruction) or very subtle, based on the careful use of language. On this subject, I think George Orwell was particularly insightful. Here he is in his beautiful essay called Politics and the English Language. It contains 50 year old examples but is just as relevant today.

“In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible. Things like the continuance of British rule in India, the Russian purges and deportations, the dropping of the atom bombs on Japan, can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of the political parties. Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenceless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification. Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers. People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: this is called elimination of unreliable elements. Such phraseology is needed if one wants to name things without calling up mental pictures of them. Consider for instance some comfortable English professor defending Russian totalitarianism. He cannot say outright, ‘I believe in killing off your opponents when you can get good results by doing so’. Probably, therefore, he will say something like this:

‘While freely conceding that the Soviet regime exhibits certain features which the humanitarian may be inclined to deplore, we must, I think, agree that a certain curtailment of the right to political opposition is an unavoidable concomitant of transitional periods, and that the rigors which the Russian people have been called upon to undergo have been amply justified in the sphere of concrete achievement.’

The inflated style itself is a kind of euphemism. A mass of Latin words falls upon the facts like soft snow, blurring the outline and covering up all the details…. Every such phrase anaesthetizes a portion of one’s brain.”

The Hollow Men slide

One of the most revealing parts of the research for my book The Hollow Men was watching the way that language was carefully planned for political effect. Some phrases were to anaethetise portions of the public’s brains, and others to evoke the desired feelings of anger, fear and resentment.

Since the book itself was the subject of some spin doctoring by the National Party, I should explain the book for people who haven’t read it. It is, in large sections, a book about propaganda.

The book is based on a huge quantity of internal National Party documents, which allowed me to write about a three-year period of that party’s history. Assisted by all the internal strategy papers, meeting minutes, e-mails and itineraries I had been leaked, I could show, in their own words, the thinking behind all the speeches, media statements, election slogans and ads and other tactics that we, the public, saw over that period. What I found was the cynicism and contemptuous attitude to the public quoted earlier from Peter Keenan, which led in turn to cynical and manipulative election tactics. In addition I could document hidden agendas, hidden political alliances with business groups and right-wing churches, the identities of the anonymous donors and much more.

I’ll use three striking examples of propaganda from the book. The first, and the whole reason I got going in the first place, was the National Party leader Don Brash’s first major speech, which was the 2004 Orewa Rotary Club speech on so-called ‘race-based privilege’. In Chapter 5 of my book, you can read the strategy discussions that led up to that speech, which had nothing to do with the supposedly urgent issues of race relations and everything to do with trying to score a poll lift for the recently elected leader. Then there was a process of carefully concocting the speech, very much along the lines of Keenan’s Politics as a War of Emotions approach. Each message planned for political effect; it was not really policy at all. And the effect was anger and envy.

In book get a close up view of the unelected strategists and speech writers for whom these tactics are simply a game, a device for raising the polls.

Having written the Orewa speech, created the planned ‘big splash’ and reaped the poll rise, Keenan confided during the election year that ‘I hate the “race based privilege” line’. National was still milking the ‘end race-based privilege’ slogan, which was one of six main election messages selected for endless repetition. But Keenan told Sinclair he thought this was ‘ludicrous when Maori are largely at the bottom of the heap’.

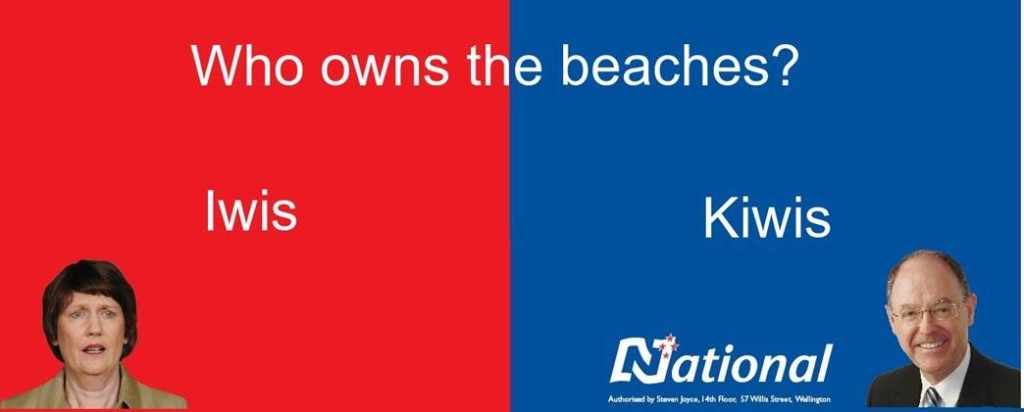

The second example of modern propaganda is National’s 2005 ‘Iwi Kiwi’ billboards – which were designed to do in two words what the Orewa speech had done in 4,973 words.

Iwi Kiwi slide

As I wrote in the book, the special power of Iwi/Kiwi – which made it the most influential of the billboards – came from the use of an extreme claim (that somehow public access to beaches was at risk) combined with the simple elegance of the words iwi and Kiwi being so alike. It also relied on another well-documented phenomenon: most people’s innate wish to be part of a group and their easily aroused feelings against people who are not in the group.28 This is apparently the case even when the ‘group’ does not exist in any practical way and is created only by political rhetoric such as ‘hardworking’ New Zealanders. The Iwi/Kiwi billboards encouraged ‘non-Maori’ to feel separate and threatened by Maori who wanted to take away their beaches, even though there was never a real risk of this. (In fact, the Labour Government was in a political fight WITH Maori, not somehow on the Maori side against the Kiwis.)

Negative stereotyping often employs anecdotes as ‘proof’ to build or reinforce prejudices. This is why National’s selection of outrageous Labour government spending – ‘Hip-hop tours, welfare bribes, prisoner compo, twilight golf, sing-along courses, taniwha….’ – tended, coming after years of similar publicity, to bring to mind a Maori or Polynesian face. After a while, a regularly maintained negative stereotype can become an enduring myth, as repetition creates its own truth.

Typically, the media commentary was uncritical and not interested in the accuracy or integrity. ‘National’s hit billboards’ were ‘striking’, ‘iconic’, ‘clever’ and ‘short, punchy and easily recognisable, if somewhat misleading in their simplicity’.22 The New Zealand Herald described the billboards as ‘elegantly simple and humorous and perfectly designed to catch the attention of the drive-by voter’. The ‘Succinct messages… cleverly presented the essence of a problem and its solution’.

But they didn’t. They billboards were not trying to raise the important issues most New Zealanders care about and they mostly did not show a real difference in policy. They were strong examples of modern propaganda, deserving a place here on the museum walls with the WWII posters.

The third and most outstanding example of National Party propaganda, was the Taxathon TV advertisements. Before I screen it, recall the theory of propaganda that explains that (quote) “The ideal messages to bypass our intellects and get inside our heads are the simple repetitive ones where our attention is caught (that is, distracted) by the music, moving pictures, surprising images and humour.”

Taxathon television advertisement played

“American film director Charles Guggenheim once wrote: ‘Ask any seasoned media advertiser and he will tell you what he can do best in thirty seconds. Create doubt. Build fear. Exploit anxiety. Hit and run. The thirty and sixty second commercials are ready made for innuendo and half truth. Because of their brevity, the audience forgives their failure to quantify, to explain, to defend.’

The worrying thing about the Taxathon advertisements is that they were treated as acceptable. Thirty years earlier, National’s ‘dancing Cossack’ advertisements had been controversial and widely discussed. The 1993 anti-MMP advertisements – with their black and white images of babies left crying and a strait-jacketed, faceless politician – also caused disquiet and debate. But in 2005 the NP advertisements were mostly taken by commentators as just clever, part of the ‘successful’ campaigning. A party could become government not because of its policies or candidates, but purely because it had the cleverest advertising people and the biggest budget.”

Underlying the tactics I wrote about was a cynical view of the public – essentially dumb punters – they referred to their target as “people who watch the TV news with the sound turned off”. This justified the conscious use of manipulation.

My main concern about this is that tactics that treat people as stupid and malleable, encourage people to act stupid and malleable. Dumbing down. The other way to do politics is to treat the public as intelligent and principled and bring out the best in people. We have good examples in National and Labour Governments of politicians who have done this, inspiring people rather than appealing to small mindedness and prejudice. The difference has been summed up as the difference between politics (implying information, debate etc) and just power. The difference between leadership and manipulation.

What can we do living in a world of propaganda?

First and most important is to increase our understanding of what is happening. The more literate we are of the techniques, the less effect they will have and the more free choices we will have. This is observing and understanding the propaganda instead of just being a ‘target audience’.

Second, I recommend mostly not trying to get your news from television. The nature of television does not assist understanding or analysis.

Third, we all need to think about and put effort into building up the ‘democratic infrastructure’ of our society so that we have alternative sources of information and stronger societal defences against the powerful interests using propaganda. This means better news media, freer and more outspoken university staff, more independent scientists and public servants, more democratic political parties and stronger and more active community organisations. Most important individually, we need to participate in society – writing letters to the newspaper and being active in politics – fighting the indifference and passivity that the National Party-style political tactics encourage.

Fourth, for people involved in politics, the challenge is to do it differently – to recognise that expedient short-term political tactics can do long-term harm to the country. I recommend reading The Hollow Men and, while feeling repelled by the cynical attitudes and tactics, think about how it can be done differently. Similarly, people in PR and media jobs can think about how they do their jobs and live by the values they want to see in the world.

Overall, free minds and open debate are the best defence against propaganda. It should not become normalised. We should expect better from our leaders and be offended whenever they shift from persuasion into the deception, falsehood and manipulation of propaganda.